Pole, Dusk

Day and Night in 2008(That tailpiece may be, like a lizard’s, detachable.)Be not wary of the pushy, that supposed excellence is a hat easily knocked off in a crowd of burghers, a polite word for the bourgeoisie. Heed not the encumbered soldiery of the damnably sly and minute meritorious advancing—they hoist up high fat bags above spindly legs and spot the landscape like question marks. Martyrs to a socius like a flying wedge formation, the heated breaths of concomitant goals, the muddy shins, the tight cheeks, and jerseys. The goals, the gaols. Reading our Saturdays away didn’t make us sissies, or think much about lying—Art dropped by with its wild arguments about Life, and Diane too, who’d lift up her blouse for a cigarette, menthol preferred. There were positives and negatives about the proximity of the horses, and the horse barn, and the stackable bales in the horse barn, all so fort da. What I think is, we lack regular injections of “myth” into the shallow molds our sad trajectories become, some quotidian mischief syringed in with a little more indebtedness than what’s offered by the speaker’s bureau, that “club.” The moon hanging up there like a crumpled horn, completely cowed by the vicious immortality of the rocketry thrown at it. I stumble out into the taiga to holler and shoo off the bombarding flies, pull mightily at udders flopping like trouser legs down out of a cloud. A barn tom minces in the stream. The cow stands square-haunched and unbetrayed. I’m not talking about Poulenc in Newark. What I recall is James Brown in Sloatsburg one whole Sunday afternoon in a whiskey-watering “tap room” where the locals burned to light into us like hornets, pure fury in a lopped-off grin. Pool cues chalked blue, scratch marks on the table, the “merry din” of the pinball machine’s mounting numericals. Now the sky is completely black, unutterably so. Curving down off into the deckle-edge of trees, mesh and means

of continuing, tolerably so

against the panoramic fusk of sleep so

that a teeming heterodoxy may, by so

channeling its wild disclosures, chart so

heroic an abeyance as mum, so

that devilish propinquity’d nod off so

affably against what is so

matte and defiant with indifference that so

clamorous a rake as a man so

struck by particularity as to kite one word so

generally against its own resounding thrall so

as to forswear any ordinary comeuppance to so

regular a ruse whilst night’s clench, so

aseptic and conniving lets go so

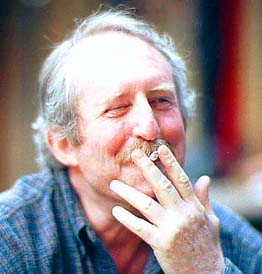

suddenly one’d think it’d lit up a cheroot, so

like day’s solitary rumpus and sluice, tenably so.

—

Flew through some pages of Tom Raworth’s shortish and breezy A Serial Biography (Turtle Island, 1977), a book I have no recall whatsoever of acquiring, and one, I think, I confuse with Aram Saroyan’s The Street: An Autobiographical Novel for no particularly indentifiable reason, similar size, vague same “era.” Raworth show’d up at Michigan in the Donald Hall days (circa 1968 or so) and proceeded to visit Andrew Carrigan’s room, where some few of us were getting wholly “took” by a succession of wild writers, asides and chortles and excitements amongst adults indicating something big “up.” Somewhere is a copy of Moving acquired shortly thereafter. What I recall is a fierce fluidity and a poem about a roiling domestic scene with the lines “taking the scissors / began to trim off the baby’s fingers.” That and the obvious (though to me revelatory) play of a title like “The Relation Ship,” words within words, words talking out the sides of they moufs. In A Serial Biography it’s the glimpses of the bombing of London, and the post-war shortages that impress: how different that is, how easy one forgets that difference. A snippet, random:

It was a bad picture, but suddenly the word ‘frontier’ made him cry. There was a foreign name that made him cry also. He wore sun glasses and did not take them off during the interval. He began to cry again during the main film, although the girl reminded him of no-one he knew; she had dark hair and was young. Outside, the cars were parked on both sides of the road. Engines started and lights came on. People were eating expensive cakes in the coffee bar. He did not know why he had cried, though ‘frontier’ seemed a reasonable thing to cry at. At night the searchlights flickered along each strand.Tiny echo of Joyce’s “Araby” somewhere there, detect’d in the typing up.